Volcanoes and Collisional Mountains

The folds, faults, and everything in-between

Have you ever wondered what the difference is between the Cascade Mountain range and the Himalaya Mountain range? Maybe you have seen news reports about volcanic eruptions and earthquakes and wonder why we cannot stop them? Well, we can’t stop tectonic plates from moving, but we can understand how they work and what their movements mean to us. Today, you’re going to learn about two types of mountains, volcanic and collisional. These mountains and the tectonic activities that produce them can be hazardous to us; however, they also offer us many benefits as well. Let’s take a “peak” behind the curtains that form mountains and what that means for us.

To start, I would like to explain a few important geological concepts. First, there are two types of tectonic plates, continental and oceanic. Continental plates are thick and buoyant, so they essentially float on the wax-like asthenosphere, which is the lower crust and upper mantle. The rocks that make them up are high in silica, so they have a felsic to intermediate felsic chemistry. Meanwhile, oceanic plates are thin but dense, so they are the plates that can be dragged down into the Earth. These plates have a mafic chemistry, so they have less silica but are rich in magnesium and iron. Furthermore, the chemistry of these plates impacts their density and how they interact with the lithosphere, the upper crust, and the asthenosphere. Second, tectonic activities of subduction and collision occur at convergent plate boundaries. At these boundaries, two tectonic plates move towards each other which causes a buildup of compressional stress. This stress gradually builds up pressure and energy over time until it is suddenly released. The sudden release of stress, or energy, happens when the built-up stress has surpassed the strength of the rocks that make up the plate. The sudden release of energy from convergent tectonic plate movement is what causes earthquakes. If earthquakes occur close to water, then the energy released can displace water and cause a tsunami to form as well. With that in mind, let’s quickly discuss how these plates work at convergence.

The tectonic activity called subduction occurs where tectonic plates come together at what is known as convergent plate boundaries. The denser plate goes downward into the crust while the buoyant plate stays on top. Subduction can occur in two scenarios: it can happen between two oceanic plates or between an oceanic and a continental plate. When subduction occurs between two oceanic plates, the older, more dense plate subducts under the younger, lighter plate. This is because the older plate is cooler, so it is denser, while the younger plate is warmer, which makes it slightly more buoyant. With an oceanic plate and a continental plate, the oceanic plate subducts under the continental plate because it is denser. Subduction produces magma because the denser plate is forced deeper into the crust and is close to or at the hot mantle. The heat from the mantle and water carried by the subducting plate causes the rocks of the subducting plate to melt. The initial magma is extremely hot and has mafic chemistry, but as it rises its chemistry and temperature changes. This is due to assimilation, which means that the felsic-intermediate rocks are also melted and join the mafic magma. This changes the chemistry of the mafic magma to become felsic to intermediate. Due to this, the magma gets cooler as it rises because energy has been used to melt the surrounding rocks. With that being said, there is another form of tectonic convergence which operates differently than subduction.

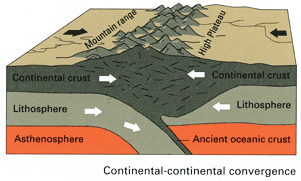

Meanwhile, two continental plates cannot undergo subduction and do not generate magma. This is because both plates are too buoyant to go underneath the other. Therefore, the plates collide into each other instead of one plate subducting the other. So, the crust goes upwards in a collisional event instead of downwards like subduction. Furthermore, magma cannot be produced if the plates are not near a sufficiently hot source, such as deep within the crust near the mantle, to cause melting. Even though magma is not generated with collision convergence, the crust is still heavily altered. With these geological concepts out of the way, let’s dive into the hot topic of volcanoes.

The volcanic mountains known as stratovolcanoes are formed via subduction at a convergent plate boundary. When a cluster of stratovolcanoes are created at these boundaries, they are not called mountain belts, they are instead referred to as arcs. At oceanic-oceanic convergent boundaries, they are called island arcs. With oceanic-continental convergent boundaries, they are referred to as volcanic arcs. Both types of arcs are not formed from tectonic uplift or crustal deformation; instead, they are slowly built up by lava flows and volcanic debris from eruptions. Internal features unique to volcanoes help subduction essentially recycle the crust, which then creates fuel for the volcano to erupt and regenerate itself and its surroundings. You see, once subduction occurs, part of the tectonic plate is melted into magma. The magma pools together in the volcano's magma chamber. Then, the magma rises through a channel called a conduit. During its journey in the conduit, the magma undergoes chemical changes, which make the melt cooler and thicker. The cooler temperature causes the magma to hold more gas instead of dissolving it. The magma then either escapes to the surface through a side channel, forming a lava dome, or it travels to the top of the volcano, also known as the main vent (“Composite Volcanoes”1). At the vent, the thick, gas-filled magma cannot easily escape so pressure builds up. When this pressure is suddenly released, an explosive eruption occurs, which creates lava flows and ejects pyroclastic debris like ash, pumice, lava bombs, and more. After the eruption, the lava flows cool and solidify, and the ejected materials settle and eventually lithify. This all contributes to the growth of the volcano and its surrounding areas. Now that you all know how volcanoes are built up from recycled mantle materials, let’s discuss a mountain type that usually reuses and reduces the crust rather than recycling it.

Mountains formed by two tectonic plates colliding do not generate new land. Instead, when the two plates collide, the crust is thrust upwards. The crust being extended horizontally in one area causes the surrounding crust to become shorter and thinner vertically. For further context, the crustal thickening upwards reuses the crust while the crustal shortening vertically reduces the crust. Therefore, this process does not recycle the crust like subduction does, instead it uses what is already available. Nevertheless, because this horizontal extension forms a crustal root beneath the mountain, it can lead to a process that does recycle the crust. After some time, this root can lead to a process called delamination, which is when the lower part of the lithosphere separates and sinks into the asthenosphere. However, these mountains cannot generate magma during delamination because it is a very slow process, and the continental crust is too thick to melt quickly (Condie2). Besides the lack of subduction and magma production, there are not many differences between collisional and volcanic mountains. Both face compressional stress from tectonic activity, which leads to deformation through ductile strain. This type of strain makes the rocks act like plastic, bending and folding without breaking. Thus, ductile strain causes deformations like folds and thrust faults for both mountain types (“Stress and Strain”5). It should be noted that compared to volcanic mountains, collision mountains face more crustal deformation because of their compressional, uplifting origins. With an understanding of the two types of mountains formed from convergence, we can explore some of the benefits and hazards they produce.

As mentioned before, both mountains and their plate boundaries create earthquakes and possibly tsunamis as a byproduct. Alongside seismic activity, stratovolcanoes produce hazards unique to them. When they erupt, all of the gases and debris are forcefully ejected out, which can create pyroclastic flows. These super-heated flows, filled with gas and volcanic rock debris, are detrimental to us and our infrastructure. Their extreme temperatures, the speed at which they travel, and the harmful effects of exposure to the released gases and particulates are what make them so dangerous. Another flow that can be destructive is lahars. This mass wasting event is filled with volcanic debris, gas, and heat and flows rapidly downhill. Both types of flows can contaminate surface water and even leach the contaminants into the groundwater. However, flowing lava is not a huge hazard because it is viscous and therefore slow-moving, so it is easy to outrun it. Meanwhile, hazards from collisional mountains are largely influenced by gravity and the weather. Some of these hazards include excessive water runoff from storms and snow melting leading to flooding, rock and landslides, and avalanches. These mass wasting and flooding events can wreak havoc on the landscape, damage infrastructure, and lead to loss of life (“Disaster Risk Management”3). With all that, there are numerous benefits we get from both types of mountains that will hopefully ease your mind.

Beyond their stunning landscapes, both mountain types provide us with vital resources for our everyday lives. Volcanoes can create new land for us from solidified lava flows and lithified pyroclastic debris. Moreover, pyroclastic debris is used in many important infrastructure materials like concrete, roof coatings, insulation, and more. Also, volcanic ash is very beneficial to vegetation and agriculture because it provides nutrients to the soil (“What Are Some Good Things That Volcanoes Do”6). Additionally, heat produced from volcanoes can be harvested as a clean energy source, geothermal energy. Collisional mountains offer us important resources as well. Mountains at higher elevations produce snow, ice, and glaciers. When these cold sources melt, we are supplied with a vital resource for our everyday lives, freshwater (“Geology of Rocky Mountain National Park”4). We can also harvest hydroelectric energy from mountain streams and rivers formed by glacial and snow melt. In theory, if a volcanic mountain has not erupted recently and does not show any activity, if it is dormant, it too could provide uncontaminated fresh water similar to collisional mountain.

Now you all know about the mountains that form from convergent boundaries, some of their hazards, and some of their benefits as well. Hopefully you all understand that although both these mountains have hazards, the way they support us, and our way of life helps balance the hazards they produce. Plate tectonics cannot be stopped, but they can be understood and appreciated for what they can provide us with. Without these mountains, we wouldn’t have a surplus of fresh water, industrial materials, fertile soil, and beautiful scenery. Below I have included some more resources about volcanoes if you’re interested in learning more. I have also made a table comparing volcanoes and collisional mountains to help you all see some of the similarities and differences. I also included a few extra facts in it that I could not fit into this article.

Rock Talk

Rock Talk